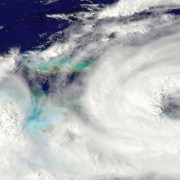

Hurricane Season Is Here

Florida’s hurricane season begins on June 1 and ends November 30. Based on historical weather records dating back to the 1950s, a typical season will average 12 tropical storms with sustained winds of at least 39 miles per hour, of which six may turn into hurricanes with winds of 74 miles per hour or more. In addition to high winds, hurricanes and tropical storms can bring torrential rainfall and localized flooding.

Localized flooding from these types of severe weather events can be exacerbated because of improperly maintained drainage systems. Residential communities and businesses can help mitigate the impacts from severe storms. One of the most important steps is the regular inspection and maintenance of drainage infrastructure. Drainage infrastructure can include inlets, discharge control structures, connecting pipes and ponds. Proper maintenance of these facilities will ensure unobstructed flow of stormwater and fully operational equipment.

Additionally, residential communities and businesses with operable discharge control structures can request authorization from the Lake Worth Drainage District (LWDD) to open these structures prior to the storm. Lowering pond levels prior to the rain event provides additional storage in ponds for excess stormwater. The LWDD recommends establishing a Drainage Committee whose role is to provide for the maintenance and operation of the community or business’s drainage system. Drainage Committees may consist of board members, residents and/or property managers. All members of the Drainage Committee should register with the LWDD on its website at www.lwdd.net/storm-response. This registration process ensures the LWDD knows who to contact and where to send important weather alerts and instructions.

During the storm, LWDD personnel will monitor canal elevations and make operational adjustments to major flood control structures as needed. Depending on the volume and duration of rainfall, expect streets, sidewalks, driveways and lawns to flood. These areas are designed to function as secondary detention areas and help to keep water away from homes and businesses. This flooding is temporary and will begin to recede after an event has passed. However, always follow emergency management instructions if told to evacuate.

It may be tempting to explore outside, for your safety and to keep roadways clear for emergency response vehicles, stay indoors until told otherwise by authorities. Do not try to walk in flooded areas. Flood water may be unsanitary and there may be downed power lines or other hazards that are not visible. Do not try to drive through flooded areas. Vehicles can become unstable and float in just inches of water. Additionally, canal banks may fail, and roadways may be impacted by sinkholes. The location of roads and sidewalks may not be discernible from canals due to the sheeting effect of flood water and life-threatening accidents can occur.

No system, no matter how well designed, is 100% flood proof but collaborating with communities, businesses and other water management agencies, LWDD can help keep you and your property safe from potential flooding.